Trouble ahead for fruit trees?

Written for the Davis Enterprise, January 22 2015

As I admired my February Gold daffodils blooming in January,

about three weeks ahead of schedule, I ruminated on the impact of the warm, wet

December and the sunny, dry January we've had so far.

In an average January we have 18.5 cloudy days. This January

we've had three. Not that most gardeners are complaining about the sunshine,

but that means that daytime highs are above average. The storms in December

were very warm, and much of the month was above average. We've only seen a few

frosty mornings so far. Overall our winter has been mild.

Unfortunately, some of our important crops and garden plants

count on having a normal amount of winter cold. Farmers are keeping a wary eye

on these temperatures. Growers of cherries, pistachios, and walnuts already

know their yields could be low this year. But the problem could extend to other

tree crops. There will be adverse impact on the state's economy. And you may

see reduced fruit production in your back yard as well.

What are the effects of low chilling units?

Fruit tree scientists (pomologists) have known for years

that many species require a certain number of hours below 45 degrees and above

freezing. The trees have evolved mechanisms that prevent dormant buds

from growing until a certain amount of chilling, and then a certain amount of

warming, has occurred.

With insufficient chilling, the trees leaf out later

(delayed foliation). Flowers don't develop properly. Flowers open over a longer

period of time. Pollination doesn't happen properly. Pollenizers don't overlap

sufficiently in bloom to provide the right pollen when the flower is receptive.

Fruit yield and quality are reduced.

It's easy to see the evolutionary adaptation to delaying

flowering until freezing weather is past. Orchardists and home gardeners should

look for varieties appropriate to their region as to the number of "chilling

hours" required. If you're gardening in coastal or Southern California, you

can't grow the same varieties that do so well for us up here. Usually do well,

that is. We average over 800 hours of chilling here most years.

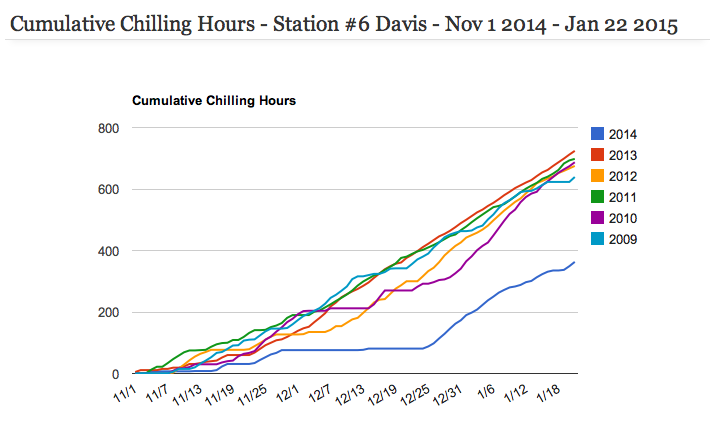

2015 is on track to have the lowest chilling hours

accumulation in many years. You can see for yourself where we stand by looking

at the weather models at http://fruitsandnuts.ucdavis.edu

Last year by January 20 Davis had 699 chilling hours, on the

way to a seasonal total of 871. This year? Less than half: 337 chilling hours to

date, and the weather forecast has warmer weather on tap for the coming week. I

had to go back to 1995 to find a year comparable to 2015. How did we do that

year? 545 chilling hours by the end of February. California's apricot

crop in 1995 was down 49%.

We've only got a few weeks left for stone fruits to

accumulate enough chilling hours. If temperatures are at or below average, we

will likely get to a little more than 500. But unfortunately the current

weather forecast shows a warming spell. Above average temperatures are not the

farmer's friend right now. As it stands, cherries and walnuts are likely to

have problems, as are some of your apples, pears, nectarines, and peaches.

Chilling units.

There's an added wrinkle. The old models for chilling hours

just counted the number of hours between 32 and 45 degrees. Temperatures below

freezing don't help. Temperatures above average weren't factored in. But

research shows that when daytime temperatures are higher than average, chilling

hours are reversed to a degree. Pomologists now measure the plant's dormancy

requirement in "chilling units." These have not been fully worked out for every

species and variety, but the bottom line is that unusually warm weather makes

things worse.

As if they didn't have enough problems already with Spotted

wing drosophila infesting the fruit, and drought affecting water supplies, California's

cherry growers got an unpleasant surprise in this regard last year. Cherries

are a high-chill crop, with most commercial varieties requiring 800 or more

hours. We had plenty of chilling hours, but high temperatures during January

and February 'undid' those. The trees' flowers didn't develop properly and

didn't set fruit. The USDA reported that California's cherry crop in 2014 was

63% below 2013. Many home gardeners had no fruit on their cherry trees last

year. 2015 looks like a repeat.

In the garden.

Other than higher prices at the grocery store, what does all

of this have to do with you?

Your backyard harvest is likely to be low, perhaps very low,

on some of your fruit trees. Others will do fine. Chilling requirements

vary by species and variety.

*

Very low chilling requirement, nothing to worry about: figs,

berries, grapes, jujube, mulberries, persimmons, pomegranates, and quince.

*

Moderately low chilling requirement, yields should be fine:

blueberries (Southern highbush, the most common here), Japanese plums, pluots

and apriums; almonds and pecans.

*

High chill types, yields likely to be low to very low this year:

many apples, some apricots, Northern highbush blueberries, sweet cherries, many

peaches and nectarines, some pears, European (prune) plums, walnuts.

Should we shift to planting low-chill varieties? Probably

not now or in the near future. It is expected that chilling hours will decrease

in the Sacramento Valley by 20 – 25% over the next several decades. But

it won't be a straight-line decline; there will be warmer winters, and colder

winters. The lifespan of a fruit tree is a couple of decades. Your kids should

probably give this some thought if they go into walnut production. You and I

probably don't need to make drastic changes in our selection of varieties.

Why not plant low-chill varieties anyway?

Because most of the best-flavored types of peaches

and nectarines have higher chill requirements, and this isn't an issue most

years. Elberta, Loring, and O'Henry peaches – all among the tops for

flavor – require about 800 hours. Rio Oso Gem and Redhaven peach and

Independence nectarine require 900 hours. The latter two are important

commercial varieties. But for home gardeners the occasional low-crop year is

more than compensated by the quality in other years. If you want some

insurance, just add a lower-chill type nearby.

*

June Gold cling peach and Goldmine nectarine can all take 450

hours or less. Red Baron peach, which has spectacular flowers and very good fruit

that ripens over several weeks, only requires 250.

or less. Red Baron peach, which has spectacular flowers and very good fruit

that ripens over several weeks, only requires 250.

*

In pears, the Asian types only need 400 – 450 hours. European

varieties Kieffer and Moonglow are fine with 400 – 500 hours; Pineapple

only needs 200. Those also have good fireblight resistance, which is important

in selecting pears. Better-known varieties such as Bartlett and d'Anjou have

higher needs at 800 and 700 hours respectively (and very poor fireblight

resistance).

*

Lower-chill apples include Anders, Fuji, Gala, Granny Smith, and

Pink Lady, all less than 500 hours. Gravenstein (700) and Honeycrisp (800) may

have poor yields this year. Many heirloom apple varieties have high chilling

requirements.

*

Harcot apricot, recommended for brown rot resistance, needs 700

hours, but the ever-popular Blenheim only requires 4 – 500.

Fruit trees aren't the only plants affected by a lack of

winter chilling. I expect there will be reduced bloom on lilacs and peonies.

Lilac varieties differ, with some having been bred for tolerance of warmer

winters, so results will vary.

In sum: nurseries and master gardeners are going to spend a

lot of time this summer answering the question "why didn't I get fruit?"

Answer: the winter was too warm for some of our favorite types of fruits and

nuts. There's always next year!

Chilling hours by type, with selected varieties (pdf)